- Home

- Laura Martin

The Ark Plan Page 2

The Ark Plan Read online

Page 2

Shawn held up three fingers, wordlessly asking if it was the third time this month that I’d had to help out Shamus.

I shook my head and held up four. He nodded. The PA system hissed and crackled, and everyone fell silent as we waited for the day’s announcements.

“Good morning,” barked the voice of our head marine, First General Ron Kennedy. I wrinkled my nose in dislike. Each compound had ten marines stationed to keep the peace and assist in brief forays topside for things like tunnel reinforcements. They were the Noah’s eyes and ears at each of the compounds, reporting back problems that arose. Of those ten, General Kennedy was my least favorite. “Today is Monday, September 1. Day number 54,351 here in North Compound.” Kennedy went on. “Please rise for the pledge.” As one, the class rose and turned to face the black flag with the Noah’s symbol of a golden boat positioned in the corner of the classroom.

“We pledge obedience to the cause,” the class chanted in unison, “of the survival of the human race. And we give thanks for our Noah, who saved us from extinction. One people, underground, indivisible, with equality and life for all.” We took our seats.

“Tunnel repairs are continuing,” General Kennedy’s voice went on, “so please avoid using the southern tunnels in section 29–34 unless absolutely necessary. Mail was delivered today,” he said, and then he paused as though he could hear the excited murmur that had greeted this news. Mail was delivered only four times a year between compounds, and sometimes less than that due to the danger of sharing the skies with the flying dinosaurs. Although I was pretty sure the ones that flew and swam weren’t technically considered dinosaurs. I remembered a science lesson where we’d learned they were really just flying and swimming reptiles, but I didn’t see what the difference was.

“As always, the mail will be searched and sorted before being delivered. We appreciate your patience as we work to ensure the safety of all citizens here in North.”

When I glanced up, Shawn was studying me suspiciously, his brow furrowed over dark blue eyes.

I tried to keep my face blank, like the mail being delivered and my being late had absolutely nothing to do with each other. But I was a horrible liar.

“It wasn’t just Shamus, was it?” Shawn hissed, pointing an accusing finger at me. “You were checking the maildrop again.”

“Shhhh,” I hissed back as General Kennedy went on to discuss the upcoming compound-wide assembly scheduled for the following week.

“You are going to get killed.” He frowned. “And all for some stupid hunch.”

“I won’t.” I huffed into my still-wet bangs in exasperation, wishing that I’d chosen a best friend who wasn’t so nosy. “And it isn’t a hunch.”

Shawn raised an eyebrow at me. “Okay,” I conceded. “It’s a hunch.” But just because year after year there’d been no mention about the disappearance of the compound’s lead scientist didn’t mean they wouldn’t, I thought stubbornly. How could I explain to Shawn the pull I felt to find out what had happened to my dad? I imagined it was similar to what it felt like to lose a limb, a constant nagging sense of something missing, a dull ache that wouldn’t go away.

“It’s been almost five years,” Shawn pointed out. “The odds that you are going to find out anything at this point are low.”

“Does that mean you don’t want to see the information I got?” I asked, trying hard to keep a straight face.

“I didn’t say that,” he grumbled, and I grinned, knowing I’d won.

“You should have at least told me you were going topside so I would know to send the marines’ body crew out for you if you didn’t make it back,” Shawn grouched. I made a face at him. The marines’ body crew was a standing joke between us. There was no such thing as a body crew in North Compound, because what lived above us didn’t leave bodies behind. The crackling of the PA system signaled that announcements were over, and I turned my attention back to the front of the classroom.

“Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd called out, and I jumped. “I can only assume you were late because you were spending your time studying for our literary analysis today. Please stand,” he said, not bothering to look up from his port.

“Busted,” Shawn hissed.

“You too, Mr. Reilly,” Professor Lloyd said. Someone snickered, and my face turned bright red as I stood. Shawn grumbled something incoherent, but he stood as well.

“All right, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said, glancing down at the port screen in front of him. “If you wouldn’t mind giving the class an explanation of the similarities between the events that transpired in Michael Crichton’s ancient classic Jurassic Park and the events that have taken place in our own history.”

“Similarities?” I asked, swallowing hard. I’d just finished reading the novel the night before, so I knew the answer, but I hated speaking in public. Facing the herd of deinonychus again would have been preferable. I wasn’t sure what that said about me.

“Yes,” Professor Lloyd said, a hint of annoyance creeping into his voice. “Quickly, please. We are wasting time that I’m sure your classmates would appreciate having to work on their analyses.”

“Well,” I said, keeping my eyes on my desk. “In Mr. Crichton’s book, the dinosaurs were also brought out of extinction.” I glanced up to see Professor Lloyd staring at me pointedly. He wasn’t going to let me get away with just that. Clenching sweaty hands, I plowed ahead. “The scientists in the book used dinosaur DNA, just like our scientists did a hundred and fifty years ago. And just like in the book, our ancestors initially thought dinosaurs were amazing. So once they had mastered the technology involved, they started bringing back as many species as they could get their hands on.”

“Thank you, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said. He turned to Shawn, who had propped one hip on his desk while he was listening to me, the picture of unconcerned boredom. Professor Lloyd noticed too and frowned. “Mr. Reilly, if you wouldn’t mind explaining the differences between Crichton’s fiction and our own reality?”

“Sure,” Shawn said, with a wide grin. “Well, the obvious one is the size of the dinosaurs, right? I mean, ours are gigantic. Almost twice the size of the ones that Crichton guy talks about.”

“That’s correct,” Professor Lloyd said, addressing the room. “As Mr. Reilly so eloquently put it, that Crichton guy based his dinosaurs off the bones displayed in museums and pictured in old world biology books. What Crichton didn’t take into account was how different our world was compared with the dinosaur’s original harsh habitat. Chemically enhanced crops, gentler climate, and steroid-riddled livestock made them grow much larger than their ancient counterparts.”

“You can say that again,” Shawn said, and the class chuckled. I didn’t laugh. The memory of my close call with the pack of deinonychus was still too fresh. They’d seemed massive, and they weren’t even one of the bigger dinosaurs. The compound entrances were set in a small clearing bordered by fairly thick forest, which made it impossible for the larger dinosaurs to get too close.

“Anything else, Mr. Reilly?” Professor Lloyd asked, a hint of annoyance back in his voice.

“Yeah,” Shawn said. “The people in the book didn’t have them as pets, on farms, in zoos, or in wildlife preserves like we did before the pandemic hit. They were mostly kept to that island, amusement park thing.”

“And why is that important?” Professor Lloyd prompted.

Shawn rolled his eyes. “Because when the Dinosauria Pandemic hit our world and wiped out 99.9 percent of the human population, it was really easy for the dinosaurs to take over. Which is why we now live in underground compounds, and they live up there.” He pointed at the ceiling.

“For now,” Professor Lloyd corrected. “Our esteemed Noah assures us that we will be migrating aboveground as soon as the dinosaur issue has been resolved.”

“They’ve been saying that for the last hundred and fifty years,” I muttered under my breath, just loud enough for Shawn to hear. He flashed a quick grin at

me. The different plans to move humanity back aboveground had spanned from the overly complicated to the downright ridiculous, but each time a new plan was brought up, the danger of the dinosaurs was always too great to risk it.

“So in summary,” Professor Lloyd said, motioning for us to have a seat, “the scientists of a hundred and fifty years ago were unaware that by bringing back the dinosaurs, they were also bringing back the bacteria and viruses that died with them. And as you all know about the disastrous devastation of the Dinosauria Pandemic, I will stop talking to give you as much time as possible to complete your literary analysis. You may access the original text on your port screens.”

I glanced down at my port screen, where the literary analysis had just appeared. Professor Lloyd was right, we all did know the disastrous effects of the Dinosauria Pandemic; we lived with them every day. I tried to imagine what it had been like back then. The excitement as scientists brought back new dinosaur species daily. The age of the dinosaur had seemed like such a brilliant advance for mankind. How shocked everyone must have been when it all fell apart so horribly and so quickly.

The Dinosauria Pandemic had hit hard, killing its victims in hours instead of days like other pandemics. It had spread at lightning speed, not discriminating against any race, age, or gender. I could just imagine how shell-shocked the few survivors were who’d been blessed with immunity to a disease that should have been extinct for millions of years. They must have thought the world was ending. And I guess to some degree, it was.

One by one, the countries of the world had gone dark as news stations went off the air and communication broke down in the panic that followed. I wondered if anywhere else had fared better than the United States. Were there underground compounds sprinkled throughout Paris? London? Africa? Were people thousands of miles away huddled together thinking they were the last of the human race just like us? I hoped so, but I doubted it.

The United States had gotten lucky to avoid extinction. With no formal government left standing, one man had stepped up to rally what was left of humanity. He’d called himself the Noah after some biblical story about a man saving the human race in a big boat called an ark. He’d arranged for the survivors to flee into the four underground nuclear bomb shelters located across the United States. And once we were out of the way, the dinosaurs quickly reclaimed the world, and we’d never been able to get it back.

I pulled up my copy of Jurassic Park on my port and flipped through the pages, looking for something I could use in my analysis. I’d hated reading Crichton’s book, and I doubly hated having to write about it. His descriptions of life topside made my insides burn with jealousy. It wasn’t fair that one generation’s colossal mistake could ruin things for every generation to come.

I was the first one to finish the analysis. I was always the first one to finish an analysis. Poor Shawn was sweating, his tongue protruding from compressed lips as he scribbled furiously. When the bell rang ten minutes later, he finally walked up to plug in his port, and I could tell from the look on his face that it hadn’t gone well.

“Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd called out just as I was slinging my bag over my shoulder to leave, “a moment, please.”

My heart sank, but I dutifully filed up to wait by the side of his desk as the last few students plugged in their ports and left. He gazed at his own port, moving his finger down the list of students, ensuring that all of our assignments had been uploaded for him to grade before turning to me with a frown.

“It didn’t go unnoticed that this was your third tardy this month, Sky.”

“I’m sorry, sir.” I hung my head.

“I believe you know what to do with this,” he said, pressing a button on his port screen. Immediately my own port vibrated, and I glanced down to see a work detail form filling my screen. There was a place at the bottom for a parent’s digital signature, but Professor Lloyd had crossed out the word Parent and instead typed the word Guardian.

“Yes, sir.” I slipped the port into my pocket. It would get signed for the following day, but I would be the one doing the signing.

I bolted for the door, and almost ran headfirst into Shawn.

“Whoa!” he exclaimed, catching my port screen deftly before it could hit the concrete and shatter, again. “Where’s the fire?”

“No fire,” I scowled, taking back my port. “Just another stupid work detail.”

“Work detail is a character-building experience,” he said sarcastically.

“Then why don’t you serve it for me if they’re so great?” I asked.

“Because my character is already flawless,” he grinned. “It would be a waste of our compound’s precious resources.”

I gave him an elbow to the ribs as we headed toward science class. We paused in the hallway to let the kindergartners totter past us on their way back from the library. Shamus waved at us shyly, and I noticed Toby Lant slumped at the back of the line, his head down. He had the greasy, unwashed appearance of a kid whose parents didn’t keep track of how often he bathed, and a hollow look that I’d seen in the mirror a bit too often. My heart hurt for him, even if he had been bullying Shamus.

“Do you have a lunch ticket?” I asked Shawn as we watched the kids’ progress down the hall.

“I have my pack for the whole week. Why?” I snatched the entire pack from him before he had them halfway out of his pocket and hurried over to crouch by Shamus. Tucking the lunch tickets into his hand, I whispered in his ear. He smiled nervously at me but nodded. After a quick ruffle of his hair, I hustled back to join Shawn.

“Why did you just give Shamus my lunch tickets? Not that I’m complaining, but I was planning on eating at some point this week.”

“I don’t think you’ll starve to death.” I grinned. When Shawn had stopped growing at five feet one inch, he’d decided that what he lacked in height he could make up for in bulky muscle. I doubted that a few missed meals would affect him. “Besides, you know your aunt could get you more. Just tell her you lost them. Shamus needed to buy lunch for his new friend, Toby.”

“Does Toby know he’s Shamus’s new friend?” Shawn asked. I shrugged. I would have given Shamus my lunch tickets, but I had lost those last week for not reporting to work detail on time.

Shawn must have understood, because he didn’t say anything else about it as we ducked into our science classroom. This was my favorite class of the day because the room had a domed skylight ceiling. Of course, the Plexiglas of the skylight had been patched, repaired, barred over, and reinforced in so many places that it didn’t really afford much of a view to the outside world anymore, but the natural light still managed to filter through, and it was a relief after the harsh fluorescents. Humans weren’t meant to live their lives underground, and sometimes my skin practically itched for the sunlight.

Soon, though, even this little piece of the outside world would be taken away when the workers began concreting over the glass. Noah had insisted that we fortify all topside surfaces. This new decree seemed silly to me. The dinosaurs had never penetrated the barrier that separated our world from theirs, so why waste the resources? Unfortunately, no one asked my opinion on the matter, especially not the most powerful man in the world.

I glanced around at the rows of plants lining the walls and frowned. They would all be dead soon unless we brought some grow lights up from the farming plots. The rest of my class filed in, all eight of them. Professor Murphy moved to the front of the room to begin trimming back a fern whose leaves reminded me of Shawn’s hair, floppy and out of control. Shawn sat down beside me and slid a bag of crackers onto my desk. He knew that I’d have skipped breakfast in order to make it out to the maildrop. When I went to thank him, I saw that he was working furiously on the homework from the day before. The crackers had the slightly chemical taste that most compound food had, but I savored every one, especially now that Shawn’s lunch tickets were gone. As the class began, I couldn’t help but wonder if I would have resorted to stealing lunch tickets

if I hadn’t had a best friend who was willing to share.

Shawn and I once joked that the entirety of our education in North Compound could be summed up into two lessons. Lesson one was some variation of a history lesson about how the human race had found itself living in underground compounds. Today’s English lesson with Professor Lloyd had fallen under that heading. Lesson two was how to actually survive in the compound. Professor Murphy’s lecture landed squarely in the second category. She started discussing the finer points of artificial turnip germination, and I zoned out immediately. Since the majority of the supplies and food for the compound was generated within the compound, lessons like this were common, but I just couldn’t get excited about turnips. From the way Professor Murphy kept stifling yawns, I had a feeling that she felt the same way.

Seven hours later, when the last bell of the day finally rang, I made my way through the crowded south tunnel to find Shawn. Being crowded was a good thing. North Compound had started off with just twenty survivors. Luckily the immunity that had saved those original twenty from the Dinosauria Pandemic seemed to pass on genetically in most cases, so our population levels were slowly climbing. I think we were at ninety-five last I’d heard. After years of teetering on the edge of extinction, the human race was making a slow but steady comeback.

I tried to ignore the fact that none of my classmates felt the need to include me in their easygoing conversations. I was an island in a sea of chatter and laughter that I wasn’t allowed to be a part of. Some of these kids’ parents had written petitions to have me banned from attending school altogether. Luckily for me, all those petitions failed. In a community grounded on principals of collaboration and equality, even the daughter of a traitor was owed an education. I wouldn’t want to be part of their stupid conversation anyway, I thought as I ducked my head and made my way into the library to find Shawn.

A library hadn’t been on the original engineer’s design plans for the compound, although they’d thought of almost everything else. There were huge spaces on the bottom level equipped with water lines and grow lights to cultivate plants, a water and electrical system that could function without any outside power or input, and even a livestock area for animals like cows or pigs. But those stalls had long ago been turned into offices and storage units since, in the chaos of fleeing the topside world, no one had thought to grab any livestock. Now the poor creatures were extinct. A cow didn’t stand a chance against a dinosaur. Which wasn’t saying much. Most things didn’t stand a chance against a dinosaur.

The Brooding Earl's Proposition

The Brooding Earl's Proposition Reunited with His Long-Lost Cinderella

Reunited with His Long-Lost Cinderella Courting the Forbidden Debutante

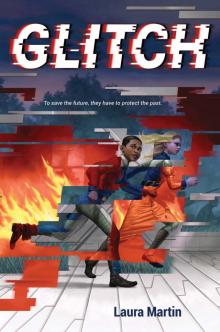

Courting the Forbidden Debutante Glitch

Glitch Flirting with His Forbidden Lady--A Regency Family is Reunited

Flirting with His Forbidden Lady--A Regency Family is Reunited The Monster Missions

The Monster Missions Falling for His Practical Wife

Falling for His Practical Wife Her Rags-to-Riches Christmas

Her Rags-to-Riches Christmas Secrets Behind Locked Doors

Secrets Behind Locked Doors Under a Desert Moon

Under a Desert Moon Her Best Friend, the Duke

Her Best Friend, the Duke An Earl to Save Her Reputation

An Earl to Save Her Reputation Heiress on the Run

Heiress on the Run The Ark Plan

The Ark Plan A Ring for the Pregnant Debutante

A Ring for the Pregnant Debutante Code Name Flood

Code Name Flood The Viscount's Runaway Wife

The Viscount's Runaway Wife An Unlikely Debutante

An Unlikely Debutante