- Home

- Laura Martin

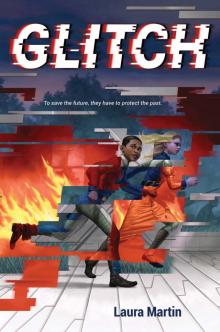

Glitch Page 2

Glitch Read online

Page 2

“Don’t worry too much about your mom.” With that she hit the button and the metal doors slid open, letting her out into the bustling hallway where all the kids who hadn’t screwed up their simulation that day were gathering their books to leave for their dinners. The doors slid shut again and the noise of the hallway was choked off instantly. Simulation rooms were soundproofed to an almost maddening degree, and now that I was alone, I could hear my own heartbeat like someone was holding a microphone to my chest. It wasn’t a new sensation by any means, but that didn’t make it any less unsettling.

I wanted nothing more than to skip the recap of my one-second failure and join the crowd heading home. My stomach gave an angry snarl to remind me that skipping lunch to study for this recap had been a big fat waste. I should have just eaten. It had been grilled cheese day too. I loved grilled cheese day. Feeling equal parts resentful and resigned, I waited until the screen in front of me showed the big green check mark that let me know my recap had been successfully uploaded before sliding off the table and heading over to the door. Waiting for the upload was part of the simulation training protocol, although it seemed redundant since as far as I knew, one had never failed to upload. Personally, I think they made us wait so we had a few moments to think things over and prepare ourselves for what came next.

The wall hummed as I walked toward it, and a second later the door slid open with an efficient click. The sound echoed up and down the corridor, letting me know the other cadets were being released too. I felt my cheeks burn a little in embarrassment, but I brushed it off. There would be time for that soon enough. I straightened my spine to my full five feet seven inches and strode out without a backward glance. So what if this was my third recap this week? It was all part of the process. We had to learn if we wanted to protect the future.

I followed the flow of cadets down the corridor and into the auditorium-style recap room at the end of the hall. Unlike the room I’d just left, this one was warm, and I felt the goose bumps on my arms melt back into my skin as I slid into a seat at the back. No need to be front and center for this. My classmates filed in around me, filling in the seats until the room was about a quarter full. I noted that three of the other kids in my year—Jennifer, Rory, and Mike—were here, a fact that should have probably made me feel better, but instead it just annoyed me. The more kids in the recap, the longer this whole mess was going to take. Besides, it wasn’t like we were all buddies who would sit together to make this whole thing more bearable. They were nice to me in the way that most people were, like it was a requirement because of who my mom was, but they were a far cry from friends. Professor Treebaun stood at the front of the room, looking none too pleased about getting stuck with this particular duty.

Once the last cadet had taken their seat, Professor Treebaun pressed a button on his tablet and the doors to the recap room slid shut, sealing us in.

“Would anyone like to volunteer to begin this particular recap session?” he asked, his sharp eyes scanning the room. I sank down deeper into my chair and made an effort to look anywhere but at him. Thankfully he called on someone else, and the room darkened as the floor-to-ceiling screen in the front of the room came to life so the entire class could watch a third-year cadet’s disastrous simulation during the Texas Revolution. Poor kid screwed up within one minute of landing in the middle of the battle for the Alamo. He’d taken a misstep and fallen backward, knocking over three men who had the misfortune of standing near the wall of the Alamo. Professor Treebaun chose that moment to freeze the screen, mid-flail, and I saw the boy visibly shrink.

“Who can tell me where he went wrong?” he asked. Five hands shot up, but mine was definitely not one of them. Treebaun scanned the room and then pointed to someone I couldn’t see in the front row.

“He forgot about the attack from the north outer wall of the Alamo complex,” came a voice I knew all too well. It took everything in me to stifle my eye roll. I did not, however, manage to do the same to my exasperated groan, and of course old Treebaun heard it.

“Something wrong, Cadet Fitz?” he asked, his voice lashing out like lightning.

“No, sir,” I said, sitting up straight in my chair.

“Good,” said Treebaun. “After Cadet Frost you can go.”

“Thank you, sir,” I said, forcing a smile onto my face. Treebaun turned his attention back to the know-it-all in the front row, and nodded for him to continue. The boy did, going on at length about every nitty-gritty detail of the epic battle. I saw Jennifer and Mike exchange looks of exasperation and almost smiled. I wasn’t the only one who found this particular know-it-all obnoxious.

“Very good, Cadet Mason,” Treebaun said, turning back to the class. “Now, who can explain the telltale flaw in the Butterfly Cadet Frost failed to apprehend?” With the press of a button, the Butterfly in question flicked onto the screen and began to slowly revolve in a circle so we could see every possible angle of his blood-splattered uniform.

There was the muffled rustle of clothing as everyone shifted nervously, and before I even realized I was doing it, my hand was in the air. Treebaun waited a moment, scanning the room to see if anyone else was going to volunteer before pointing at me.

“The blood on his jacket,” I said.

“Go on,” Treebaun prompted.

“It’s too red,” I explained. “If you look closely, you can see that his jacket is dry, not wet. He was disguised to look like he was injured in the battle, but blood dries brown, not bright red.”

“Very good, Cadet Fitz,” Treebaun said almost reluctantly, turning back to the screen. “This particular Butterfly was modeled after a real one caught by our commander in chief about eighteen years ago. He was one of the first members of Mayhem we ever caught.” Everyone leaned in a little, including me, to get a better look at the guy. We all knew about the group that called themselves by the name Mayhem. But their leader, location, and members were a mystery. Their organization was even older than the Academy, which made sense since their very existence made us so necessary. We were charged with protecting history at all costs, while they were happy to change history for the right price. There were still the sporadic attacks by misguided vigilantes, but for the most part every active Butterfly was part of Mayhem. Which meant that over the years, the attempts to alter history had become increasingly more organized and better planned, which made Butterflies that much harder to spot. The only thing we had going for us that they didn’t was that our technology and a lot of money was spent to stay one step ahead of them on that front. Unlike us, Mayhem used pieced-together equipment that often didn’t allow them to time travel with the precision that we did, and, of course, they didn’t have Chaos Cuffs. The thought of those cuffs made me smile, and I found my hand going instinctively to my hip, where a set had hung during my simulation. Superheroes had capes that marked them as the good guys. Glitchers? We had cuffs. The repercussion track for the Alamo kid started to play, and I stifled a yawn.

“Next up is Cadet Fitz,” said Treebaun, not needing to consult his tablet for my particular simulation since he’d watched it in person. The press of a button and the screen changed from the bloody battle of the Alamo to the serene inside of Ford’s Theatre.

“This was your third attempt at the Lincoln assassination, was it not?” said Treebaun.

I gritted my teeth and shook my head. He knew full well this wasn’t my third attempt. “No, sir,” I said, “my fifth.” A ripple of stifled laughter went around the room, but I kept my spine ramrod straight, my eyes dead ahead. I could almost hear my mom’s voice in my head coaching me. Confidence is a skill, Regan. The more you practice it, the better you get. Learn to maintain an air of total control despite the circumstances swirling around you.

“Right,” said Treebaun. “Let’s begin.”

The room darkened again and the screen shimmered, zooming in on an image of me sitting in my blue dress. The recap began.

Recaps shouldn’t turn my stomach anymore, but they still

did. Watching myself on that screen was like having a million ants crawl underneath my skin, and not just any ants, but the fire ant variety that liked to bite. And the feeling was that much worse now that I knew Elliot Mason was sitting in the front row. I rolled my neck from side to side in an attempt to dispel the feeling as I watched myself spot the Butterfly and exit my seat at the theater.

Did I really wrinkle my face like that when I was thinking? It made my already turned-up nose look even more piglike. Charming. And man, did the back of my hair look stupid in those tight bouncy ringlets. I ran my palm over my smooth blond strands and caught myself wrinkling my nose in the exact way I’d just found obnoxious. I rubbed it with the back of my hand, grateful that for simulations at least I didn’t have to actually curl my hair or wear the dress. If I ever got to do an actual mission, I’d have to do all that. The prep would be real, and the bite marks the Butterfly on-screen was so nicely carving into my arm wouldn’t magically disappear when the simulation ended. Treebaun paused the screen on the image of a wide-eyed John Wilkes Booth and turned back to the class.

“Cadet Fitz missed this particular simulation by one second. Who here knows how she could have saved herself that second?”

Just like I knew it would, a slim brown hand in the front row shot into the air.

“Cadet Mason again,” said Treebaun.

“Had she used the alternate staircase, she would have arrived in plenty of time to apprehend her Butterfly,” said Cadet Mason, and I could just picture the smug look on his stupid face as he said it. Treebaun changed the screen to a diagram of Ford’s Theatre and did a quick overview of all the ways the top balcony could have been accessed before turning on my repercussion track.

The repercussion track was different every time, depending on how badly you’d screwed up, and really, as my mom liked to point out, it was just a bunch of guesswork. Its purpose was to show the Glitcher what their actions could cause in the future.

Without Lincoln’s death, things got surprisingly nasty. My one-second mistake would cause the North and South to never fully reconcile in the aftermath of the Civil War. Eventually, a second civil war would take place, this one twice as devastating and deadly as the first, making what should have been the United States of America so divided and weak that it was easily conquered. All because of one teeny-tiny, should-be-insignificant second. I watched this alternative history spiral out in flashes and blips and bit my lip. Treebaun was right—I did have to be perfect. Which was a problem, because while I was a lot of things, I was a far cry from perfect. I sighed. It would have been nice if, for once, I’d knocked this simulation out of the park, especially with Elliot Mason sitting front and center.

The screen changed to the next student, and I relaxed a little in my seat. If Elliot was in here, then he’d screwed up too, and I was going to enjoy watching him squirm. Treebaun progressed quickly through each student’s recap and repercussion track, and I watched a botched Kennedy assassination simulation, a Watergate mess, and a rather iffy situation involving Ben Franklin, but none of them were Elliot’s. Finally it was over, the lights went on for good, and Treebaun turned to us, his lined face serious as he took the time to look each of us in the eye.

“You will not make the same mistake again, will you, cadets?” he asked.

“I will not,” I responded in unison with the rest of the room. There was no other correct answer. Everyone stood up, but I stayed in my seat a heartbeat longer. He’d forgotten to show Elliot’s simulation. How had he forgotten? Treebaun never forgot anything. The rest of the kids filed out the doors as I sat there fuming. But then I saw Elliot get up, and I grabbed my stuff and shouldered my way through the crowd and out. No way I was going to allow him to gloat face-to-face. A few people grumbled, but I made it through the door and headed down the hallway toward home.

Rounding a corner, I almost ran headfirst into two cadets. I mumbled an apology and was about to keep going when I caught a glimpse of their expressions and stopped. Both of their young faces were drained of color, their hands visibly shaking as they fumbled to zip up their jackets. I recognized them as being a few years below me, but I couldn’t remember their names. It was obvious that their recaps and repercussions had been bad ones, I thought, trying to place each of them in the simulations I’d just watched. The boy I recognized from a pretty bloody World War I battle, and I thought the girl was the one who’d gotten herself killed during the Kennedy assassination. I could have been wrong, though. I could sympathize. Watching myself die on-screen, even if it was just a simulation, always made my insides go cold and hard, like I’d swallowed an iceberg. These kids looked like they’d swallowed the one that had taken down the Titanic, and I couldn’t help but feel a tug of sadness for them. They’d never asked for this life. None of us had, and it wasn’t the first time I wondered what it would be like to have a life other than this one. To have the freedom to choose my own path based on my strengths instead of being crammed down one that seemed to do nothing but highlight my weaknesses. I shook my head, pushing the thought away. I was a Glitcher. I was the daughter of the commander in chief. I didn’t get an option of another life, and I’d decided a long time ago that I wasn’t going to let that sour the one I did get. This was the hand of cards I’d been dealt, and I was going to play it for all I was worth, even if that meant watching the same recap of Lincoln’s assassination until I died of embarrassment.

Long gone were the days when someone could be born with the time-traveling gene and go unaccounted for. Everyone saw the mess that made, and it had taken years to get history straightened back out. Some things had been too far gone to correct and history had just had to bear the scars. Germany was still upset about the whole Hindenburg mess, but as our professors were quick to point out, the world needed a tangible reminder of what happened when time travelers pranced through history like a bunch of unchaperoned kindergartners on a field trip. Thankfully, right around the time that Mayhem started recruiting, the government stepped in and started regulating things.

Now everyone was checked for the gene at birth. They poked your heel, smeared some blood on a slide, and checked to see if you were one in a half million. If you were born with the teeny-tiny DNA glitch that allowed you to slide in and out of time like a knife through butter, you were handed over to your country’s branch of the Academy. We were part of the United States branch, but there were Academy branches just like ours hidden all over the world. One of the most important and influential treaties of all time had made it possible for each country’s Academy to regulate its own Glitchers, with the understanding that a Glitcher was only allowed to protect their own country’s history. Of course, things always got a bit hairy when multiple countries were involved in a historical event. For example, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand that kicked off World War I had taken three weeks of negotiations and a lifetime of headaches, according to my mother. So sending your child off to the Academy was an honor above all others, but that meant that parents were allowed to see their kids only twice a year during the special visitation times the Academy carefully orchestrated with enough security to sink a ship.

One of the few exceptions to that rule, of course, was me. I’d been born on Academy property, the daughter of the Academy’s commander in chief. My dad had been a Glitcher too, but he’d died on a mission before I was born. Mom didn’t like to talk about him, so we didn’t. I’d asked her once what would have happened to me if I hadn’t tested positive for the active Glitching gene, and she’d been purposefully vague. Leading me to believe that a little blond-haired baby girl would have mysteriously ended up on the doorstep of an orphanage somewhere. While that may seem cruel and heartless to most, I knew it was just protocol. You couldn’t live or work at the Academy unless you had the Glitch gene. Period.

My heart gave a painful tug as I looked at the two little faces in front of me. I could practically see the tears pressing against the backs of the girl’s eyeballs, and before I could think better of it, I

found myself putting a companionable arm around her shoulders and squeezing. She jumped about a foot at my contact, her curly brown hair whipping across her face as she turned terrified green eyes up to meet mine. The boy beside her was scowling, caught up in the memories of his own recap, no doubt, but when he saw me his expression changed to one of worried wariness. A moment later his hand snapped to his forehead in a salute. I ignored it and gave the girl a smile that was meant to be encouraging but now felt stiff.

“It gets easier,” I said. “Every time. It gets easier.”

She nodded but didn’t look at me, and I could tell from the rigidity of the muscles beneath my hand that I hadn’t convinced her in the slightest. How old was she? Eight? Nine, tops? Third-year cadets seemed like such babies now, even though I was only a few years older than them. This would be their first year doing full simulations, and I knew that was a hard transition. The girl’s bony shoulders felt as fragile as a bird’s wing under my hand, and I released it and stepped back.

“It really does get better,” I assured them both. “Promise.”

“Stop that,” quipped a male voice behind me. “Don’t you know that you don’t salute the commander’s daughter?” I turned to see Elliot Mason. He was staring at the two kids, a smirk twisting his mouth. “She’s not anyone important. She just thinks she is.”

“Lovely to see you too, Elliot,” I said, smiling too brightly as I turned to the wide-eyed cadets. “Forgive him,” I said. “Elliot has the personality of a constipated toad, and he struggles with remembering his manners.”

Elliot’s dark brown eyes narrowed into angry slits. “You aren’t funny, cadet,” he sneered, and I saw him stand up straighter in an attempt to offset the three additional inches of height I’d had on him since we were both eight. I fought the instinct to roll my eyes. It wasn’t my fault that I’d inherited my mom’s height, and just to press the fact, I straightened my spine so I could look down at him. It was then that I noticed that our audience had disappeared. The kids I’d been talking to had melted into the crowd, and it was just Elliot and me. Which, I reminded myself, was a situation my mother had given me strict instructions to avoid. The best way to prevent a conflict with Cadet Mason is to keep your distance, she’d said, like it was easy to do in a class as small as ours. We were two of ten students in our fifth cadet year, and avoiding him was next to impossible.

The Brooding Earl's Proposition

The Brooding Earl's Proposition Reunited with His Long-Lost Cinderella

Reunited with His Long-Lost Cinderella Courting the Forbidden Debutante

Courting the Forbidden Debutante Glitch

Glitch Flirting with His Forbidden Lady--A Regency Family is Reunited

Flirting with His Forbidden Lady--A Regency Family is Reunited The Monster Missions

The Monster Missions Falling for His Practical Wife

Falling for His Practical Wife Her Rags-to-Riches Christmas

Her Rags-to-Riches Christmas Secrets Behind Locked Doors

Secrets Behind Locked Doors Under a Desert Moon

Under a Desert Moon Her Best Friend, the Duke

Her Best Friend, the Duke An Earl to Save Her Reputation

An Earl to Save Her Reputation Heiress on the Run

Heiress on the Run The Ark Plan

The Ark Plan A Ring for the Pregnant Debutante

A Ring for the Pregnant Debutante Code Name Flood

Code Name Flood The Viscount's Runaway Wife

The Viscount's Runaway Wife An Unlikely Debutante

An Unlikely Debutante